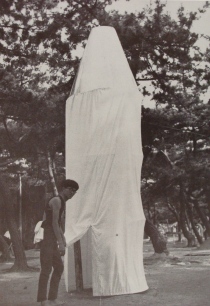

The tent

February 22, 2010

Helio Oiticica, Eden, 1969.

According to Mircea Eliade, the cabin, the forest, and darkness, are worldwide recurrent scenarios where rites of initiation take place, archetypal images that “express the eternal psychodrama of a violent death followed by rebirth” (ELIADE, M. 1995, Rites and Symbols of Initiation, pp. 35-37). The initiatory cabin represents not only the belly of a devouring monster who digests the novice, but also the womb, signifying the return to an embryonic condition, to a virtual, pre-cosmic mode.

Inside the initiatory cabin, the novices are taught about the sacred, death, sexuality, survival, a knowledge that is often expressed with the learning of a new language, and loss of memory of the former identity.

Centre of the World

January 30, 2010

Hélio Oiticica, Tropicalia (1968) and Eden (1969). Saburo Murakami, Sky (1st Gutai Outdoor Exh., 1956).

The “nostalgia for paradise” is inherent to the structure of the “centre of the world”. Mircea Eliade states that every dwelling is a “centre of the world”, the place of passage from the profane mode of being to the non-profane mode of being, symbolically the place that connects earth and heaven. For this reason, “every ‘construction’, and every ‘contact’ with a ‘centre’ involves doing away with profane time, and entering the mythical illud tempus of creation”, since the spontaneous passage between earth and heaven was, in illud tempus, a privilege of all mankind.

Eliade also speaks of two kinds of traditions, “one group of traditions that evinces man’s desire to place himself at the ‘centre of the world’ without any effort, while another stresses the difficulty, and therefore the merit, of attaining it”. Man’s desire for placing himself naturally and permanently in a sacred place – at the “centre of the world”, at the core of reality and, through a short cut, transcend human condition – which was easier to satisfy on the frame of ancient societies, became more difficult to achieve on subsequent civilizations, with notions such as initiatory trial corresponding to figurations such as the initiatory cabin, the labyrinth or the mandala.

Bichos and Caminhando

January 20, 2010

From the series Bichos (1960-63); Caminhando, 1963.

Lygia Clark viewed the gestures of manipulating the Bichos as the chance for the common man to have an immediate life-experience (“vivência”) of his inner sense, an exercise to develop the expressive gesture in what she called “reliving the ritual”: “The spectator no longer projects or identifies himself with the work. He lives the work and, living its nature, he lives himself, inside of himself”. The manipulation of the Bichos enables the spectator to surpass mechanical time, bringing forth the time of “a life-experience that carries a living structure within itself”. She would also refer to this “living moment” as the point in which the clock’s hands stop, forgetting the passage of time, and marking the “point of the real”, statements that suggest the suspension of mundane or profane time as a condition to experience one’s inner sense.

While the spatial animated articulation of planes in the Bichos (Creatures) turns the surface into an “organic body”, a “living entity”, with Caminhando (Walking), the experience of cutting a Moebius Strip would deepen into “the experience of a limitless time and of a continuous space”, presenting a “single kind of duration of time, the act; (…) [in which] nothing exists before nor afterwards”. Maintaining the gratuitousness of the gesture, kept clear of any significance, the spectator will immediately realize, at the very instant of the act, the sense of his action. In Caminhando, the instant of the act is not renewable, and only the instant of the act is living: “The instant of the act is the only living reality within ourselves. Gaining awareness is already the past”.

Hang glider to ecstasy

January 16, 2010

Hélio Oiticica, Proclamation of the Parangolé. Rio de Janeiro, 1965.

Oiticica took the word parangolé from the inscription entitling an assemblage built by a homeless. The term would name Oiticica’s comprehensive search for environmental totalities and for the environmental participation of the spectator. However playful, the adoption of this word ascribes intelligibility to an otherwise meaningless or secret language, and to its subsided inventor or culture.

The term parangolé does not merely assign the interest in the “popular constructive primitivism”, but denotes the intent to distinguish the dynamics that underlies the “totality” (or “objective foundation”) of those “primary constructive nuclei” – that is, “the pluri-dimensional relation between ‘perception’ and ‘imagination'”. This relation is complementary to the process of regression into the pre-linguistic consciousness, of suspension of the discursive devices (analytic, rational), and of retrieval of the situation of spontaneity that the creation of a new verbal language, unknown to others, necessarily implies.

Parangolé: winged project for a total life experience. Oiticica at Mangueira.

With his interest in dance, “experience of the utmost vitality”, Oiticica parallels his vital need of de-intellectualism with his need for a free expression, and he refers the correspondence between, on one side, improvisation, immersion in rhythm, the complete and vital identification of gesture and, on the other side, the obscuring of the intellect “by an internal individual and collective mythical force”.

Haroldo de Campos compares the parangolé to the Hagoromo mantle of feathers, the central iconographic element in a legendary story of the classical Japanese theatre, Nô. According to Mircea Eliade, the complex of plastic representations with the sense of flight points out the idea of ecstatic or magical flight, and integrates a universally diffused symbolism of ascension which expresses two purposes, “transcendence and freedom, both the one and the other obtained by a rupture of the plane of experience, and expressive of an ontological mutation of the human being”, primarily conveyed by the abolition of weight.

The full-void

January 15, 2010

Lygia Clark (1920-1988)

“Whenever you feel empty, don’t fight against the void. Don’t fight against anything. Let yourself remain empty. Little by little you’ll be filled until you get back to the normal state of the human being, which is the creative state”.

“Quando você se sentir vazio, não lute contra o vazio. Não lute contra nada. Deixe-se ficar vazio. Aos poucos você vai se preenchendo até voltar ao estado normal do ser humano que é o criativo” (CLARK, 2005, exh. cat. Da obra ao acontecimento, p. 23).

each day, the day by day, is the avant-garde, you know?

January 15, 2010

Hélio Oiticica (1937-1980). What I do is music

(exh. cat., O q faço é música, Galeria de arte São Paulo, 1986, catalogue raisonné Projecto HO).

“The day by day itself, for me, is the building of a work, the complete day is the work. Since there is no longer the avant-garde movement: each day, the day by day, is the avant-garde, you know?”

“O próprio dia a dia, para mim, é a construção de uma obra, o dia completo é a obra. Como também não existe mais o movimento de vanguarda: cada dia, o dia a dia, é a vanguarda, entende?”